Time to Return

Temporal philosophies between samsara and progress; sprinkles on the Everything Bagel.

This is a second instalment in a series; read Part I here.

“Time is an illusion.” —Albert Einstein

In the preface to her seminal essay collection, Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968), Joan Didion opens with W.B. Yeats’s poem The Second Coming, from which she borrows her title, adding: “for several years now certain lines from the Yeats poem… have reverberated in my inner ear as if they were surgically implanted there.” And, for some years now, I have found myself relating, even if the circumstances are obviously different than they were in 1965-67. Still, since late 2016 or so Yeats’s poem has been affixed to my fridge, and when we moved last summer I took it down and put it in the box with the fridge magnets, knowing I will just put it back up again. Its time has not yet passed.

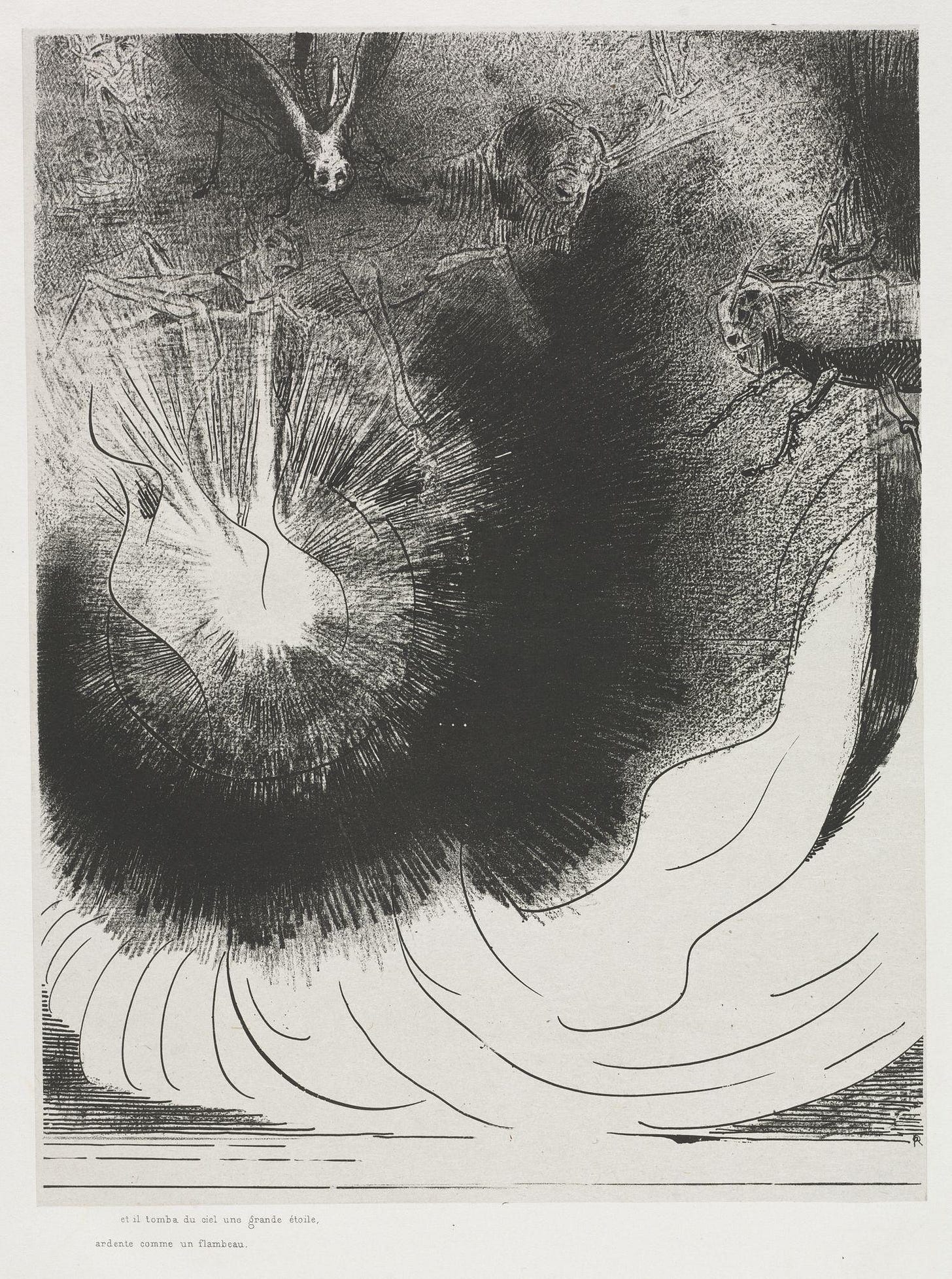

The poem is millenarian in spirit, its imagery Biblical and apocalyptic. Didion described her experience of the mid-1960s as the first time she experienced “atomization”—things falling apart—and I think I know now what she meant. It’s not an overt and clear threat or event that can be named and identified, but rather a mood, a diffuse sense of confusion, a sense that the familiar order of things is disintegrating, dissociating, losing the thread. It’s in the zeitgeist—the spirit of the times.

Yeats described it all aptly and almost too prophetically. And yet, and this is a crucial bit, I don’t believe in apocalypses. I don’t think we’re living at the end times or on the brink of some irreversible human extinction event. Thresholds, after all, come in many shapes and ways. Not every historical transition need herald a zombie-dystopian-wasteland, and as a rule, they do not. The landscape of 13th century Europe, with its plagues and wars and famines, was a far more fitting setting for crying out “the end is nigh!” in the streets—and yet, the world did not end then, either.

This seems especially important to spell out, given this moment we find ourselves in. I too, feel a shift in the quality of time; I too worry about the shape of things, the centre that “cannot hold,” and the changes all this bodes to our daily lives, sanity, and future. But, crucially, I believe that a shift in our paradigms of time is just as likely as an actual change in the texture of history. Indeed, if we want to step outside the binaries of “future is good/ future is bad” mindset, and cultivate some other ethic of engagement with the present moment, new ways of thinking about time are necessary.

...Things fall apart; the center cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

[…]

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

W. B. Yeats, 1919

Philosophies of Time

The first part of this series opened with a discussion of the “game of dice” episode in the Sanskrit epic, the Mahabharata, as a way into thinking about time from a decidedly different angle. Indic philosophical traditions tend to view time as cyclical, and the succession of distinct “ages” or yugas as part of a greater cosmological pattern of repeated creation and destruction. I will get back to the epic in the next instalment of this series—for it has much to offer us, by way of both philosophy of time and its ethical implications—but first, it is worth addressing the bigger question directly: why are we talking about philosophies of time at all?

Casual talk about an impending apocalypse—be it man-made or not, technological or ecological, mystical or deterministic—seems to have infiltrated all levels of cultural discourse. Eco-anxiety is on the rise; mental health is in a crisis; the economy is floundering, globally; geopolitical tensions are increasing; conversations about AI safety and “alignment” are taking a serious turn, not only for nerds now. In more fringe quarters, even the current hot wars in the Middle East and Ukraine are viewed through decidedly apocalyptic lenses.

One might well attribute this ferment to the prevailing mood of the “fourth turning”—the idea that, as a function of generational patterns, every fourth quarter of a century, on average, sees the disintegration of old ideas and institutions, particularly those that no longer work. This theory first appeared in a 1997 work by historian Neil Howe and political satirist Willian Strauss, and has gained considerable traction in the past couple of years, perhaps for obvious reasons. While some criticize it as not scientifically robust enough, for others it dovetails both with culturally observable events and with alternative approaches to history, which question long-taken-for-granted truisms, such as the myth of progress.

The curious bit about the fourth turning hypothesis is that it is not really about the “end times”—after all, it subscribes to a cyclical view of time and history, not a linear one. In fact, many of the prophecies and predictions currently bandied about in public discourse—often pulled from Indic, Indigenous, and other non-Abrahamic sources—are similarly taken from cyclical time systems. It seems innocuous enough, to put the two in conversation, but in truth there is a significant philosophical difference at play. Cyclical notions of time and history make space for periods of chaos and destruction, yet these are normally never finite; they do not, fundamentally, describe the end of time and matter in the same way as linear-time systems do.

Why should we care? Well, the way we think about time is not arbitrary; it is indicative of the ways in which we think about reality and our place in it more broadly. Time is where physics and metaphysics intersect, for our concepts of time are inseparable from how we think about life on earth and its range of possibilities—whether among our fellow humans, or in a bigger, cosmological sense. This, in turn, has implications both for our ethics and our psychology. In the simplest terms, how we think about time is how we think about history, human agency, the good life, and what sort of conduct does or doesn’t make sense under these circumstances.

On the most personal, lived experience level, our orientation to time determines our orientation to the future. I would argue that cyclical views of time, on the whole, give us better tools to cope with uncertainty, to weather periods of chaos and disintegration, and to develop resilience. Cyclical views of time and history put less stress on “progress” or eschatology, and leave more room for the varieties of human experience and diversities of flourishing. They help us acknowledge difficult periods without automatically defaulting to nihilistic or pessimistic stances towards reality, simply because they contain a wider range of philosophical and psychological possibilities.

What Time Is It There?

Isn’t time the same all over? Well, I suppose it depends who you ask. Time is a dimension of our experience, certainly. The way we think about time is easy to take for granted, but even in the West, the metaphysics of time have only recently taken the shape we are most familiar with.

For one, the idea that time is linear and finite is baked into the very fabric of Western culture. Though “the West” is a broad category, extending well beyond the confines of Northern Europe, its cultural focus in the past two millennia had been mostly on traditions that favour a certain “beginning-middle-end” structure of history. The Abrahamic religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—all tend to view time as flowing resolutely in one direction, sometimes with a very clear endpoint in mind.

Christianity, for example, started out as an extremely millenarian sect, with early followers awaiting the return of Jesus as the Messiah within their lifetimes, as we know from some of the early gnostic texts and Greco-Roman accounts. This messianic anticipation transformed over time, and toned down as the religion consolidated doctrinally and politically. And yet, ideas such as the “end of days,” the Second Coming, and the Final Judgement are integral to Christian cosmology and eschatology, and for some groups remain a central characteristic of the tradition.

Of course, one need not be religious or reared within any specific doctrine, to be immersed in this worldview; it is, at this point, simply a part of the Western cultural heritage. Even our current scientific models align with this linear view of time, envisioning the beginning of the universe as a Big Bang, and its end, in the impossibly distant future, as a “heat death.” (There is a caveat here, of course, coming from the field of quantum physics, but we shall set it aside, for now, as all of that is still hotly debated and hasn’t trickled down into mainstream culture or consciousness.)

As things stand, the eventual finality of both the material and the temporal is one of those beliefs about reality that seem so commonplace, so natural, within most discourses in the Western paradigm, that we don’t normally think of it as a belief at all. (Of course, most does not mean all; there have been some notable dissenters from this view—

discusses a few in a recent essay, as well as adding her own feminist anti-progress stance to the discussion).Though we take our conceptions of time largely for granted, the last major paradigm shift regarding the nature of time in the West occurred fairly recently—in the 19th century. In the past two to three centuries, Western cosmological thinking underwent some remarkably extreme metamorphoses. Among other things, in this relatively short period we went from thinking about human history in spans of thousands of years, to spans of millions and hundreds of millions of years. This change did not occur seamlessly, either, but was a matter of bitter controversy in the second half of the 19th century and well into the early 20th—as those who had read Inherit the Wind in middle school might recall (and even now, some groups continue to resist this, scientifically robust, worldview).

The major breakthrough came not from work on evolutionary theory, as one might imagine, but actually from the field of geology. While 19th century scientists still estimated the age of our planet to be between 20 and 400 million years (current scientific thought pegs it at about 4 billion), their findings expanded the total vista of reality dramatically. Suddenly, in this vast new landscape of time processes such as evolution or fossil formation became comprehensible, while the centrality of the human species was increasingly questioned and relativized.

This triggered a profound paradigm shift across all disciplines of thought. Among other things, thinking about time in this way added fuel to the religious crisis of confidence (began in the Enlightenment period), and necessitated a wholly new metaphysics and cosmology. I would venture to say that we are still in the process of formulating them; a cosmology, after all, is not merely the rattling off facts about physical and geological processes, but also an understanding of what it means for our own human existence within these parameters.

Linear vs. Cyclical Time

As historical accident would have it, around the same time as all these radical upheavals were happening in the realm of science, Indic and other Eastern spiritual and philosophical texts were becoming increasingly available in the Western world—in part on account of colonialism, in part on account of increased global travel, trade, and socio-cultural exchange. It seems almost serendipitous that, as the West was discovering geological time via innovations in technology and science, centuries- and millennia-old Sanskrit texts that calculated the age of the universe in the millions and billions of years were likewise coming to the attention of Western scholars.

Notably, while Indic traditions have concepts such as “the end of an age” and teach of successive cycles of creation and dissolution, they aren’t really apocalyptic in the same way Western concepts of time can be. The doctrine of the yugas or temporal ages in Hinduism and Buddhism, for example, maintains that while periodic cycles of creation and destruction succeed one another, the universe itself is infinite. Periods of being and non-being ebb and flow like aeon-long inhalations and exhalations. Galaxies spin up, explode, expand, die, and spin up again. This is a significant departure from a view which posits that all time, matter, and existence are ultimately finite, flowing steadily from a single primordial beginning to an incontrovertible future end.

Setting aside the nuanced history of 19th century colonial exchange, for now, another difference between the linear and cyclical philosophies that stands out is the different ways in which each conceives of time as a quality of existence and experience. Cyclical time, to be clear, does not mean that exact same set of conditions or events repeats eternally (as one Nietzsche would have it). Rather, the cyclical position envisions time, like matter, as progressing through multiple cycles, each broken up into a series of stages, from inception to decay and dissolution, with the seeds of each successive cycle planted in the rich humus of the last. It allows for change, evolution, and infinite variation within the framework of recurrence.

Meaning & Metaphysics

Theories of time are deeply vested with the metaphysics and the spiritual goals or intellectual positions of their respective traditions. For example, various Eastern meditative practices aim to train one’s mind to perceive oneness in multiplicity, and to attend to the continuous paradox that is phenomenal experience. This includes, for example, experiences of timelessness or time dilation and contraction, an ‘expanded’ sense of the present moment, etc., precisely because these systems draw a distinction between the everyday, mundane perception of time and the essential or fundamental nature of all categories of perception.

Similarly, the myth of progress, though it appears to be a secular idea, is a direct heir to linear conceptions of time and history, and in particular to the Christian doctrine of Providence. (This is by no means a novel idea; what may be novel is acknowledging that some assumptions we make about reality are not “common sense” or “scientific” in a simplistic sense, but actually have a history to them.) Ironically, while secularized notions of linear time are more aligned with current scientific thought (pace quantum mechanics), they narrow our possibilities for meaning considerably. In rejecting outmoded and limiting theological framing (second coming, final judgement, and eternal salvation/damnation), the purely materialist view has little to offer us in turn. Evolution, for example, is not a conscious process, but a natural one, wherein great leaps are achieved at random and by mutation; attempts to theorize or “optimize” such processes tend to lead down a rather dark path towards racism, eugenics, and ethno-nationalist fantasies.

Other attempts to distill meaning within secularized linear time include progress-adjacent theories about the “spirit”of history (à la Hegel) or of economics (be they Marxist or “free market”)—but these, too, are borderline theological. In fact, nearly all meaningful orientations within secular narratives of linear time place a great deal on an individual’s capacity for imagination and psychological resilience in the face of a vast, unconscious universe—precisely because in a materialist view the locus of consciousness is only found within human psyche, and not anywhere else. This is in stark contrast with cyclical time systems, which tend to emphasize the pervasiveness of consciousness well outside the boundaries of the human mind.

The association of time and consciousness is not accidental. Our consciousness, at least in its mundane, everyday aspect, unfolds in time. Our conceptions of selfhood are by and large temporal; we tend to think of ourselves as having a past, a present, and a future. We are, to paraphrase T.S. Eliot, at once defined by memory and desire; we tend to seek and derive meaning from strings of events arranged in temporal, causal chains, as these confirm our agency as well as our interconnectedness to other people, events, and traditions.

This is why time that is broken up or threatens us with sheer overwhelm reveals the vulnerability and contingency of all our identity categories. What is a self unmoored from the tethers of history, memory, or relationship? What holds together a partnership, a family, a community, or a society, if not the time spent together, the events shared, the joys and hardships weathered? When these are frayed and convulsed by shortened attention spans, increased hours spent with screens, less downtime, more information, greater social isolation, general social mistrust, decaying cultural narratives, etc., it is no wonder that our sense of self (as well as of others) becomes similarly frayed and strained.

Everything, Everywhere

The personal, experiential significance of our conceptions of time is illustrated in a spate of recent films and TV shows, such as in the absurdist sci-fi Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022), the quirky dramedy Palm Springs (2020), the fantastically mind-bending Arrival (2016) and even in the edgy Russian Doll (2019). The common thread in these very different works is that they all play with our conventional notions of time and consciousness, be it through exploring the idea of the multiverse, the primacy of language in shaping perception, or in the classical scenario of a time-loop (Groundhog Day-style, but with more nuance).

In all of these we encounter characters who are confronted with time that does not pass as expected; time that is nonlinear, simultaneous, or else is repetitive and disintegrating. Deep existential anxieties and questions of meaning surface. Is the future fixed in place? Can the world get better? Can we ever truly see one another? Are relationships doomed to fray and fail? What does it mean to be kind, in a world that doesn’t make sense? Do our choices really matter?

Everything Everywhere All At Once hones in on this point especially well, making the case that anything imagined is potentially (or actually) existent—thus giving us the multiverse. As such there is, theoretically, no limit to the alternative paths one can take, other than the limits we impose on ourselves. This might sound cheerily optimistic, but actually it is a radical free-will position, and one that advocates for making a major leap of faith as a matter of ethics. One’s full potential at any specific moment is deemed both an unknown and a multiplicity; as such, an individual is responsible for generating one’s happiness and meaning. To pin down any possible reality out of an infinity, one must act on it as if it were already real.

Not only that, but the film suggests we choose our own reality every moment of every day, and we must keep on choosing even when nothing makes sense and it seems like there are no options to choose from; having faith in one’s ability to choose is what enables the leap in the first place. This is the meaning of Waymond’s scene in the film, and of his character more generally, whose humanism is at once absurd and singularly effective in the face of meaninglessness and chaos. It doesn’t matter that it doesn’t make sense to be kind or empathetic; like most human values—love, art, friendship, grace—they don’t need to “make sense” because they are ethical goods in and of themselves. Still, they become real only when we act on them.

The Myth of Endings

There is much more to say about how our conceptions of time guide our ethics or coping mechanisms, and I will pick up this thread in the next essay of the series, in which we go back to the Mahabharata for a short spell, to see what else it has to teach us about the Kali Yuga, or the “age of disintegration.”

For now, however, I leave you with the idea of endings as such; how we think about them matters, even on a purely visceral level. It occurs to me, and maybe it’s just my own bias here (I’d be curious to know how others feel) that being able to “let go” of something—be it a situation, a person, a bad habit, a past grief, a painful experience, a mistake, a failure, an image of oneself that no longer works—seems easier in the context of a cyclical, periodic metaphysic of self and/or reality. The cyclical view of things leaves space for the possibility of returning—at some other time, with another mindset, in another capacity. Not redoing, for no one can enter the same river twice, but revisiting. There is a balance here between change and stability, between the revolutions of free will and the comforts of repetition.

For the same reason it seems hardly coincidental, that, as far as philosophical responses to varieties of existential malaise go, in the West the more extreme responses have included nihilism and pessimism of various stripes, while in the East the extremes are represented by forms of asceticism or hedonism. Why should that be? Maybe this is a tad simplistic, but I suspect this is because nihilism and pessimism are responses to finite time—a time that is bound to end, and what is worse, its ending is not vindicated by any kind of meaning. Extremes of asceticism and hedonism, on the other hand, are responses to infinite time, and reflect a desire to transcend it into some extra-temporal quality of (non)being, be it via renunciation or through sensory fullness.

This is a rather telling difference. Both sets of approaches react to a metaphysic of time, and each has its own mythology of endings; but, operating from different myths, they offer us different possibilities for human coping with problems such as meaninglessness, disintegration, or “atomization,” to return to Didion’s definition. One offers communion within a conscious, inherently meaningful universe, allowing for a variety of tools with which to counter ennui and fragmentation; the other places the burden of meaning on the shoulders of the individual as a discrete and isolated mind, and on her personal capacity for beauty, patience, grace, imagination, and resilience. At the same time, the former makes us question our agency and even sense of autonomy; the latter allows for perhaps more radical freedom. Which is more valuable? Can we benefit from both, somehow?

Is one metaphysic more true than the other? Both could be supported by objective physical data (or its lack), as by subjective experiential data (or its lack). I have certainly seen people go from one system to the other as a result of profound, life-changing experiences, as well as a result of purely intellectual, philosophical conclusions. My personal bias is in favour of that which life-affirming, and broader in its possibilities, but, in these times of anarchy and revelation, no preexisting time philosophy may be quite good enough. We might have to invent our own.

I don’t think about time, it is rather amorphous and bendy to me. This is partly because I personally experience time as a fluid concept, except in particular states of consciousness wherein we cling to it as it forms part of our identity. Probably because of my own experiences of timelessness, I see how our world is so heavily dependent on its concept. What if we stop to notice the ever-increasing creative representations of simultaneously existent alternate realities, worlds, and dream states? What does that say about a process already clearly underway? I can think of so many films in the past decade that demonstrate this. Pullman’s “His Dark Materials” remains ever present in my mind. It challenges the religious structuralism that oppresses the human spirit through the gateway of other times and spaces. Some part of us collectively knows that old structures must dissolve. As we collectively start to understand the bendy-ness of time we must allow the dissolution of all our attachments to what we believe time to be.